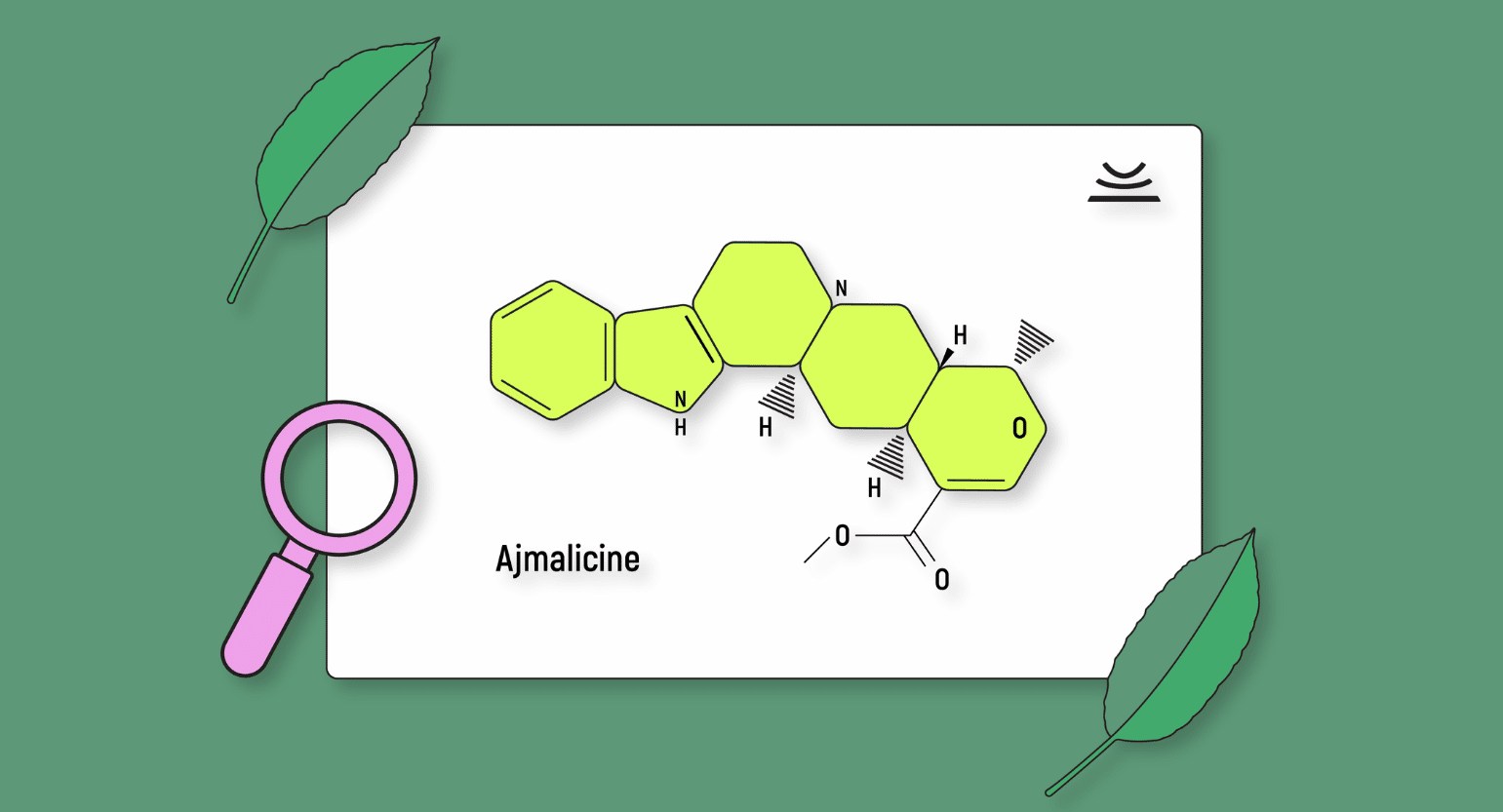

What Is Ajmalicine?

Ajmalicine is an alkaloid, a group of compounds with at least one nitrogen atom, and a physiological effect on the human body when consumed. Ajmalicine is one of over 40 alkaloids found naturally in kratom, which comes from the Mitragyna speciosa tree. It’s primarily used in medicines designed to treat high blood pressure.

What Does Ajmalicine Do & How Does It Work?

Ajmalicine is an alpha-1 adrenergic receptor antagonist, meaning it affects certain receptors in the nervous system when ingested. Also known as alpha-blockers, these antagonists prevent the tensioning activity of the hormone norepinephrine.

When this hormone is left unchecked, the walls of arteries and veins can harden slightly, causing high blood pressure and an increase in heart rate. Other smooth, involuntary muscles can also be affected. Alpha-1 adrenergic receptor agonists prevent the effects of norepinephrine, leaving the user feeling more relaxed.

In addition to relaxing the circulatory system, ajmalicine can improve blood flow and decrease pulse rate, providing a sense of relaxation.

Where Does Ajmalicine Come From?

Ajmalicine is found naturally in several different plants, including kratom, devil peppers (of the genus Rauvolfia), and several species of periwinkle (of the genus Catharanthus).

Which Kratom Strains Are Highest in Ajmalicine?

For the most part, the kratom industry is primarily concerned with levels of mitragynine and 7-hydroxymitragynine, its two primary alkaloids. Much less is known about the concentrations of minor alkaloids, including ajmalicine.

That said, ajmalicine primarily acts as an alpha-1 adrenergic receptor agonist [2], meaning it is a depressant for smooth muscle tissue [1]. The result is a sense of relaxation via suppression of the peripheral nervous system. Since red vein strains are most likely to induce a sense of relaxation and calmness, the likelihood is that red kratom strains are highest in ajmalicine. Some of the most relaxing red vein strains include Red Maeng Da kratom, Red Bali kratom, and Red Thai kratom.

What Other Plants Contain Ajmalicine?

Much of the ajmalicine used to treat hypertension is derived from certain species of periwinkle, whose root systems produce ajmalicine and other important alkaloids. Although the specific concentrations are unknown, Ajmalicine is found naturally in kratom.

As mentioned above, devil peppers, which belong to the genus Rauvolfia, also contain ajmalicine and other alkaloids.

It’s also in certain plants in the coffee family (Rubiaceae), including cat’s claw (Uncaria tomentosa), the Sri Lankan flowering plant, Petchia ceylanica, and Ochrosia oppositifolia, which is native to certain parts of Asia.

Is Ajmalicine an Opiate?

No, ajmalicine is not an opiate. While other alkaloids in kratom have opioid-like effects, ajmalicine is not one of them. It acts solely as an alpha-blocker, reducing norepinephrine’s effects in the body. The mechanism of interacting with receptors in the body is similar to opioids, but opioids and ajmalicine act on different receptors and have drastically different effects.

Is Ajmalicine Safe?

Ajmalicine is relatively safe to consume. It’s in many different prescription medications that treat hypertension, and some individuals take it daily to help manage high blood pressure.

Side Effects of Ajmalicine

Relatively few side effects are associated with ajmalicine, but they do show up in some users. These include dizziness, low blood pressure, nausea, and sweating. These adverse effects tend to appear more readily with larger doses.

How Much Ajmalicine Should I Take?

You should always consult your doctor for dosage recommendations if you’re taking ajmalicine via prescription medication for hypertension. Most people who purposefully take ajmalicine take it via a prescribed medication, so following your doctor’s instructions is crucial for safe use.

If you’re taking ajmalicine via kratom, the specific concentration of this minor alkaloid is typically unknown, and it’s not the primary reason most users consume kratom. The kratom dosage can depend on many things, including your expected effects, tolerance, body weight, and more.

Smaller doses, between 2 and 4 grams, are more stimulative and boost energy and focus. In comparison, larger amounts, between 4 and 8 grams, provide more sedation, relaxation, and pain relief for most users. You can begin with a small dose of around 2 grams of kratom powder and slowly increase it until you get the desired effects.

How Long Do the Effects of Ajmalicine Last?

Taking ajmalicine by itself in prescription medication typically doesn’t produce any immediately noticeable effects. The user’s average heart rate tends to come down, as does the blood pressure, within 2 to 7 days of regular use.

If you’re instead getting ajmalicine via kratom powder, the effects of kratom can last from 2 to 6 hours, depending on a few factors like your tolerance and sensitivity. Kratom’s relaxing effects aren’t specifically attributed to ajmalicine, so it’s difficult to say how long ajmalicine is active in your body.

Wrapping Up: Ajmalicine — A Minor Kratom Alkaloid With Medicinal Purposes

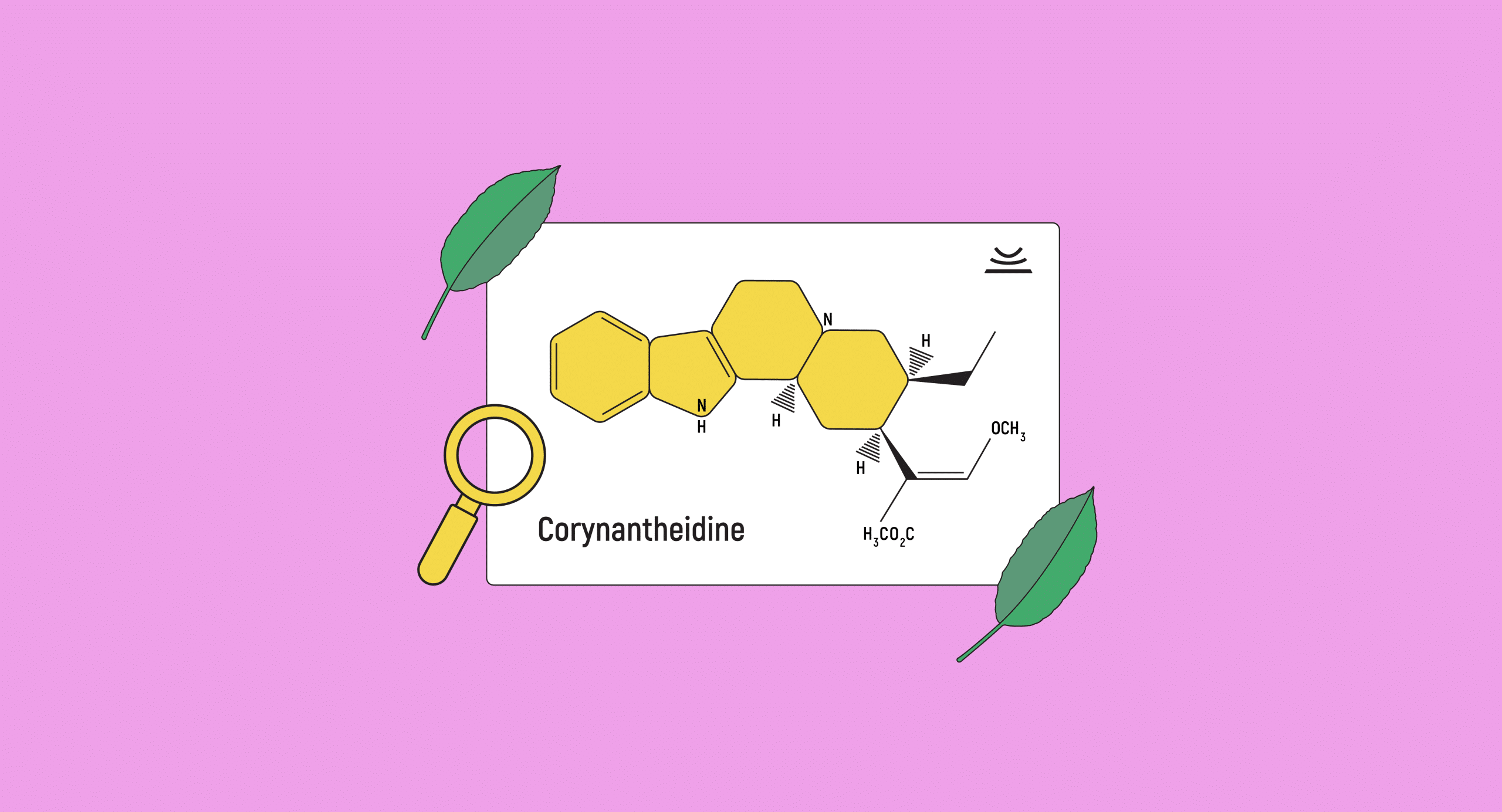

Ajmalicine is a minor alkaloid found naturally in kratom, and it also appears in several other plants, including periwinkles and devils peppers. It is predominantly used in prescription medication to treat hypertension, as it interrupts the effects of norepinephrine, which can cause a restriction of blood vessels.

Ajmalicine may play some role in the relaxing effects of kratom, as it can reduce blood pressure and naturally bring down the heart rate. However, the sedative and calming effects many kratom users look for are more likely from the impact of major alkaloids, like 7-hydroxymitragynine.

- Alpha 1 Adrenergic Receptor Antagonists. (2018). In LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

- Roquebert, J., & Demichel, P. (1984). Inhibition of the α1-and α2-adrenoceptor-mediated pressor response in pithed rats by raubasine, tetrahydroalstonine and akuammigine. European journal of pharmacology, 106(1), 203-205.