Bottom Line: Prioritize Your Sleep

The bottom line: sleep disorders are far more common than they should be. The most common causes are distress, poor sleep habits, and chronic pain.

The data shows that people who prioritize their sleep tend to develop healthier dietary habits, experience more enjoyment and less stress and worry, exercise more, and get sick less often [2].

Sleep experts recommend aiming for around 7-8 hours of sleep each night [3].

How Much Sleep Do I Need?

In the following table, you’ll find detailed information about the amount of sleep an individual needs according to their age group.

| Age Group | Recommended Hours of Sleep Per Day |

| Newborn (0 – 3 months) | 14 – 17 hours |

| Infant (4 – 12 months) | 12 – 16 hours per 24 hours (including naps) |

| Toddler (1 – 2 years) | 11 – 14 hours per 24 hours (including naps) |

| Preschool (3 – 5 years) | 10 – 13 hours per 24 hours (including naps) |

| School Age (6 – 12 years) | 9 – 12 hours per 24 hours |

| Teen (13 – 18 years) | 8 – 10 hours per 24 hours |

| Adults (18 – 60 years) | 7 or more hours per night |

| Adults (61 – 64 years) | 7 – 9 hours |

| Adults (65 years and older) | 7 – 8 hours |

Sleep Satisfaction & Duration: How Well Are We Sleeping?

How Well Are We Sleeping? It turns out that most people don’t sleep as well as they’d like.

One study found that 62% of adults aren’t satisfied with the quality of their sleep, and only 10% of respondents claimed to be sleeping exceptionally well.

Here are the figures:

- 6 out of 10 adults experience daytime sleepiness at least twice per week [1].

- In 2019, 67% of adults reported waking up at least once at night [1].

- In 2020, global sleep satisfaction rates varied greatly — the most satisfied was India, with 67% of respondents claiming to be getting a good night’s rest. Japan was the least satisfied, with just 30% [4].

- 63% of Canadians report worry/stress as the main factor that impacts their sleep quality [1].

- Between 30 to 40% of adult Americans report insomnia symptoms at some point in a given year [5].

- Short-term insomnia has an estimated prevalence of 9.5% in the United States, but about 1 in 5 cases of short-term insomnia transitions to chronic insomnia, which can persist for years [6].

- As of 2022, one in three American adults (33%) — representing about 84 million people — described their sleep as “fair” or “poor.” 35% reported their sleep was “good,” while the remaining 32% described their sleep as “very good” or “excellent” [2].

How Long Are We Sleeping?

The ideal sleep duration is different for everybody, as it depends on the individual’s lifestyle and the changes throughout a lifetime. A generally valid assumption is that individuals obtain the right amount of sleep if they wake up feeling rested and perform well during the day.

However, experts at the National Sleep Foundation suggest people between the ages of 18 and 64 should be getting between 7 and 9 hours per night [3].

Older generations require less sleep — experts recommend between 7 and 8 hours each night.

So how do the figures stack up? How long are we actually sleeping?

In 2020, the average adult reported 6.9 hours of sleep on weeknights and about an hour extra (7.7 hours) on the weekends [4].

Compared to 2019, the average sleep duration was 12 minutes longer on the weekends and 6 minutes on weeknights [4].

Very few Americans are getting the recommended 7–9 hours of sleep each night — just 35%, according to a recent survey [2].

People with kids sleep less than people without kids. 67% of parents were found to sleep fewer than seven hours — compared to 58% of those without children [2].

Men are less likely than women to report issues with sleep (51% vs. 41%, respectively) [2].

Postmenopausal women tend to experience poorer sleep quality. 27.1% of postmenopausal women have difficulties falling asleep compared to 16.8% of premenopausal women. Postmenopausal women also have more trouble staying asleep (35.9% vs. 23.7%, respectively) [7].

Statistics on Sleep Habits & Routines

One of the simplest methods people use to optimize their sleep is a concept called “sleep hygiene.” This involves minimizing all the factors contributing to sleep disruptions — like reducing the room temperature at night, avoiding screens or sources of blue light before bed, and optimizing one’s routines around bedtime.

So how are people approaching sleep hygiene? What do the numbers suggest?

Mattress quality matters — a lot. 92% of Americans who report having “excellent” sleep over the past 30 days are extremely or mostly satisfied with their mattress. This figure declines steadily among those who report poorer sleep quality [2].

Adults who stick to a bedtime routine sleep better. About 67% of people who report “excellent” sleep quality in the past 30 days say they go to sleep and wake up at the same time every day, while only 47% of “poor” sleepers do so [2]. Moreover, 43% of “excellent” sleepers report they follow their bedtime routine seven days a week.

Comfort is King. An American survey found the top reasons contributing to difficulty sleeping were related to physical comfort — having to use the bathroom (42%), physical pain or discomfort (34%), and body temperature regulation (27%) [2].

People worldwide prefer the same tactics to ensure a good night’s sleep. In 2020, watching TV, sleep apnea therapy, and having a sleep schedule were the most implemented lifestyle strategies to end the day [4, 8].

Making Sleep a Priority

Over half (55%) of Americans say getting a good night’s sleep is a “major priority” for them — prioritizing it more than other lifestyle factors, such as spending time socializing (45%) or eating healthy (40%) [2].

Women are more likely than men to say sleep is a major priority (61% vs. 48%, respectively) and report being more worried about sleep.

Shocker: Those who make sleep a priority sleep better. Study respondents who claim getting a good night of sleep is a major priority were twice as likely to report “excellent” or “very good” sleep (40%) compared to those who don’t (21%) [2].

Statistics on The Impact of Sleep Disorders

Sleep is critical to maintaining optimal health. It gives time for the body to perform maintenance — repairing damaged muscle fibers, cleaning out metabolic buildup in the arterial and neurological systems, and reconsolidating memories and information in our higher brain networks.

When we experience disruptions in sleep, our ability to perform this maintenance becomes hindered — this can result in a wide range of side effects over time.

Here’s what the data tells us:

According to the 2018 Harris Poll, the most notable impact of lack of sleep is looking tired, followed by feeling moody/irritable, lacking motivation, and being unable to focus [4].

In 2022, 55% of adult females in the U.S. stated that their sleep significantly impacted their mood, while 42% of adult males reported the same. Also, almost a third of study respondents said sleep greatly impacts their exercise habits and ability to have fun. About a quarter say it significantly affects their family relationships and eating habits [2].

The Long-term Consequences of Disordered Sleeping

Increased risk of chronic health disorders. The cumulative long-term effects of sleep loss and sleep disturbances have been linked to various adverse health effects, including high blood pressure, diabetes, obesity, depression, heart attack, and stroke [9].

Weight gain. One study found that, by age 27, individuals who slept less than 6 hours were 7.5 times more likely to have a higher body mass index [10].

Increased risk of diabetes. According to the Sleep Heart Health Study, middle-aged and older adults that sleep 5 hours or less were 2.5 times more likely to have diabetes than those who slept 7 to 8 hours per night [11].

Increased risk of alcoholism. Adults with chronic insomnia report excessive stress, depressive symptoms, anxiety, and increased alcohol use [12, 13]

Memory problems. It’s no secret that sleep disorders can induce adverse changes in cognitive performance. Sleep deprivation not only affects attention and working memory, but also alters other cognitive functions, such as long-term memory and decision-making [14].

Slower reaction times. Lack of sleep is known to affect physical reflexes, fine motor skills, and judgment [15].

Reduced moral reasoning. Research shows that partial sleep deprivation can severely impair a soldier’s capacity for mature and principled moral reasoning compared to a well-rested state [16].

Sleep & Mental Health Statistics

Perhaps the most dramatic impact of sleep is on our mental health.

50% of Americans who rate their emotional or mental health as “excellent” or “very good” also report excellent or very good sleep generally over the prior month [2].

The impact of sleep on mental health is a negative feedback loop. Adults who rated their overall mental health as “fair” or “poor” were six times less likely to sleep well than adults who rated their mental health as “excellent” or “excellent” (8% versus 50%, respectively) [2].

People who sleep well score higher on life satisfaction ratings. Among those who report “excellent” or “very good” sleep over the prior month, 84% also rate their current life satisfaction highly (seven or higher on a zero to 10 ladder scale) [2].

One-third of U.S. adults worry “a lot” or “some” about falling asleep. Worrying about sleep relates to sleep quality — 69% of those who report having “fair” or “poor” quality sleep in the last 30 days say they worry about sleep “a lot” [2].

The Economic Impact of Sleep Disorders

Sleep disorders significantly impact the U.S. economy. Poor sleep-related health conditions are associated with substantially higher healthcare utilization and expenditure rates.

A study published in the Journal of Sleep Disorders estimated that the overall incremental healthcare costs of sleep disorders in the United States are around $94.9 billion.

Moreover, according to the 2022 State of Sleep Health in America Survey, those who report higher-quality sleep are less likely to skip or miss work.

Workers who typically get a poor night’s sleep — estimated to be 6.2% of the U.S. workforce — report 2.29 days of unplanned absenteeism each month compared to 0.91 days for all other workers.

The American economy loses an estimated $44.6 billion annually in unplanned absenteeism due to poor sleep among workers [2].

Statistics: What’s Causing Us To Lose Sleep?

According to the Philip’s Global Sleep Survey, in 2019, the leading cause of poor sleep quality worldwide was worry or high stress (27.1%), followed by a poor sleep environment (20.1%), busy schedules (18.6%), late-night entertainment (18.1%), and certain health conditions (16.1%).

Worry/Stress

Stress is a major cause of insomnia and disordered sleep. Americans who experience much stress in one day are twice as likely to sleep poorly at night than those who don’t experience stress [2].

As many as 81% of Americans report that excessive mental activity — thinking, mind racing, or anxiousness — has interfered with their sleep [2].

Mental health conditions such as depression and anxiety increase the chances of poor sleep quality by 57% [2].

Sleep Environment

Several environmental factors are known to impact sleep quality; we’ll delve into some below.

Room temperature

Regulating a room’s temperature can go a long way in ensuring a good night’s sleep. Our thermoregulation system is intimately linked to the sleep regulation system, as it also follows our circadian rhythms [17].

In other words, changes in the temperature of our skin are related to our sleep-wake cycle. When we are preparing for sleep, there’s a slight drop in body temperature [18]. The lowest body temperature is reached a few hours before waking up. The body temperature continues to rise throughout the day, peaking in the evening.

Therefore, an inadequate room temperature increases the chances of waking up at night. This can even affect healthy humans without any sleep disorders [19].

Noise

According to research, loud noises during the night — whether they come from traffic, nearby neighbors, or problems in your own home — can reduce the quality of your sleep, make you wake up more frequently, and even trigger the release of stress hormones [20].

What’s more interesting, research suggests that intermittent sounds — such as an occasional honking or revving car— are more disturbing than continuous noise. This insight might be related to study findings that young adults who live in urban areas may be chronically sleep-deprived to some degree [21].

Light

Human sleeping patterns are deeply related to the 24-hour circadian rhythm — a series of chemical/hormonal changes triggered in response to light or dark. For example, when the sun rises, our bodies produce cortisol, a hormone that makes us awake and alert. And when the day ends, and there is no more sunlight, our brains produce melatonin — the sleep hormone — making us feel relaxed and ready to sleep.

Strong evidence shows that artificial light exposure at night causes suppression of melatonin, increases sleep onset latency, and increases alertness. All this results in an evident deterioration in sleep quality and disturbance in the circadian rhythm [22].

Entertainment/Technology

Technology use before bed is causing us more sleep disorders than ever. According to a 2020 global survey, around 40% of respondents reported using their phones right before falling asleep or as soon as they woke up [8].

The people who use their phones for at least 30 minutes after the lights have been turned off and those who sleep with the phone near their pillow have a statistically significant poor sleep quality [23].

Sleep Apnea

In 2020, people reported lower insomnia, snoring, and chronic pain rates than the previous year. However, sleep apnea rates remained almost the same [8].

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is one of the most prevalent sleep disorders, affecting approximately 3% to 7% of men and 2% to 5% of women in the general population [24].

Of those who reported having sleep apnea, 65% have never used sleep apnea therapy to treat their disease or are no longer using it [1]. In fact, around 30% of people with sleep apnea don’t even think treatment is necessary [8].

However, those with sleep apnea wake up twice as much as those without sleep apnea. 41% of the people with sleep apnea are significantly less satisfied with their sleep than those without sleep apnea [8].

Physical Pain

Physical pain can be a primary cause or a consequence of sleep disorders. This means the relationship between pain and sleep is bidirectional — pain can disturb a good night’s sleep, and disturbed sleep increases our sensibility for painful stimuli [25].

An epidemiologic study on insomnia showed that sleep complaints are present in 67-88% of chronic pain disorders, and at least 50% of individuals with insomnia suffer from chronic pain [26].

According to the Sleep Foundation, sleep disturbances in chronic pain patients are characterized by longer sleep onset, frequent and prolonged awakenings after sleep onset, shorter total sleep duration, reduced sleep efficiency, and poor overall sleep quality.

Chronic back or neck pain and allergies affect sleep quality, but not as significantly as headaches. Headaches almost double Americans’ likelihood of saying they had a stormy night’s sleep — 46% vs. 29%, respectively [2].

The COVID-19 Pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic has changed the way we sleep. In 2020, a share of adults worldwide reported they took longer to fall asleep due to the pandemic — 68% of respondents in Central America, 49% in America, 47% in Africa, 42% in Europe, 40% in Australia, and 24% in Asia [27].

Young people experienced more insomnia during the pandemic. 48.5% of adults aged 18 to 24 years reported they took longer to fall asleep due to the pandemic, while only 26.9% of adults aged 55 to 64 experienced this [27].

Statistics on Sleep Aids & Medications

Based on the prevalence of sleep disorders, it’s no surprise some of the most popular supplements and prescription medications in the world are centered around facilitating sleep.

In 2022, about 8% of adults in the United States reported that they used sleeping aid prescription medication to help them sleep, while 11% of adults reported using non-medicinal sleep aids like tea or melatonin [2].

Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (2005 – 2010) found that people with a doctor-diagnosed sleep disorder were five times more likely to use prescription sleeping pills than those without a diagnosis (16.3% vs. 3.1%, respectively) [28].

An analysis of the pharmaceutical market as of 2020 showed that, among all European countries, Sweden reported the highest consumption of hypnotic sleep aid medications (70.1 daily dosages per 100,000 habitants), followed by Iceland, Norway, and Luxembourg.

Melatonin

Melatonin is a sleep-regulating hormone produced by the pineal gland in the brain. It plays an essential role in the circadian rhythm — the sleep-wake cycle that determines when we are awake, alert, tired, and sleepy.

Melatonin is one of the most popular natural sleep aids nowadays — from 2008 to 2020, melatonin sales have almost tripled in the U.S. [29].

CBD or Marijuana

Moreover, the Philip’s Global Sleep Survey 2020 revealed that less traditional sleep aids have become more common — for example, 15% of the total respondents have tried or currently use either marijuana or CBD oil to better their sleep.

Herbal Supplements

Valerian, lavender, hops, ashwagandha, and chamomile are other popular natural remedies that alleviate sleep disturbances [30, 31].

Non-Medical Sleep Aids

According to the State of Sleep in America Survey, the most popular non-medical sleep aids are air conditioners or open windows (35%), noise machines (20%), sleep supplements (18.3%), and special sheets or blankets (13.3%) [2].

The Consequences of Sleep Aids

The long-term use of prescription sleep aids has been associated with other health problems, such as cardiovascular disease, headaches, balance impairment, and drowsiness [28].

The more prescription sleep aids one uses, the more likely one needs them. The 2017 Poll on Healthy Aging showed that 31% of respondents who regularly used sleeping medication stated they had difficulty falling asleep 3 to 7 nights in a typical week [32].

Sleep Statistics by Age

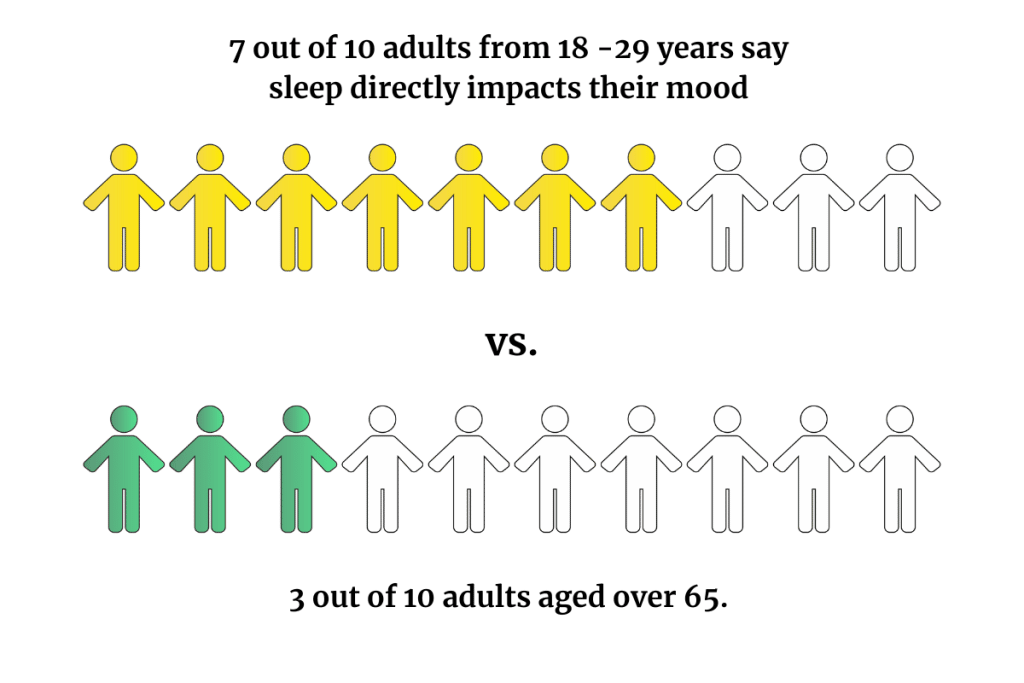

Young adults under 30 struggle more with sleep and stress. And their difficulties sleeping affect their daily lives — nearly seven in 10 say sleep directly impacts their mood, compared to three in 10 adults over the age of 65 [2].

Younger Americans are more likely to experience stress than older people. Majorities of those ages 18 to 29 (64%), 30 to 39 (57%), and 40 to 49 (52%) say they experienced stress the previous day, compared to 37% of adults ages 50 to 64 and 24% who are 65 and older [2].

Higher stress levels may help explain why younger adults are less likely than older adults to report a quality night’s sleep, more likely to report trouble sleeping, and less satisfied with their sleep.

The perceived impact of sleep on life outcomes also varies by age group:

Adults aged 18 to 29 are twice as likely to say that sleep significantly affects their mood than adults 65 and older (68% vs. 31%, respectively) [2].

Younger adults are also more likely to say sleep has a significant impact on their health (59% of 18 to 29-year-olds vs. 31% of those over 65), physical activities (39% vs. 18%), ability to have fun (46% vs. 19%), family relationships (33% vs. 18%) and their healthy eating habits (28% vs. 16%) [2].

College Students’ Sleep Statistics

University students tend to suffer from sleep regularity, quantity, and quality problems, which can affect their academic performance. These problems are related to typical changes due to maturational, psychosocial development (associated with the processes of individuation and socialization), and academic factors [33].

In 2020, a national U.S. study examined sex and ethnic/racial differences in sleep quality and the association between sleep quality and body mass index. The study revealed that female students have a poorer sleep quality than male students.

Regardless of gender, it’s more common for Hispanics & Whites to wake up feeling rested than racial/ethnic minorities. According to the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report of January 2018, 79.3% of Asian, 75% of American Indian/Alaska Native, and 77% of Black students sleep less than 8 hours on an average school night. In contrast, only 72% of White and 70% of Hispanic students report sleeping less than 8 hours [34].

This data matches the results of a study carried out in 2017 at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, where 7,626 students (70% female; 81% White) between the ages of 18 to 29 years participated. In this study, 27% of participants described their sleep quality as poor, 36% reported obtaining less than 7 hours of sleep per night, and 43% said it takes >30 minutes to fall asleep at least once per week. 62% of participants met the cutoff criteria for poor sleep; however, females showed higher rates (64%) than males (57%).

The ACHA’s Reference Group Data Report of 2021 surveyed 32,313 students and revealed that about 7.6% of respondents had extreme difficulty falling asleep for 7 of the last 7 days.

Moreover, in 2017, 51% of US medical students reported poor quality sleep [35].

Another study published in the Journal of Epidemiology and Global Health revealed a concerning 76% prevalence of poor sleep quality among medical students in Saudi Arabia.

During the survey period, 36.6% of students said they went to bed at midnight, and 33.1% said they woke up at 7:00 am. However, for the majority (73.4%), actual sleep duration was less than 7 hours, with a mean of 5.8 ± 1.3 hours.

Elderly Sleep Statistics

Studies indicate that only 12% of aged people don’t complain of sleep problems, and only about 57% report their sleeping problems to their treating physicians. More data shows that poor sleep quality is the third most prevalent health problem in aged people after headaches and digestion disorders [36].

However, the 2022 State of Sleep in America Survey revealed that only 24% of adults aged 65 and older reported “fair” or “poor” last night’s sleep quality [2]. They were also much more likely to report “excellent” or “very good” quality of sleep the night before the survey than those aged 18 to 29.

In 2017, 23% of older U.S. adults surveyed reported “occasionally” using sleep aids. The most common type of sleep aid used by this age group is over-the-counter sleep medications (17% of older adults use them occasionally vs. 5% use them regularly). This is followed by herbal remedies (8% of occasional use and 4% of regular use) [32].

5 Tips for Better Sleep

Insert a short paragraph on sleep hygiene’s benefits and tips to achieve it.

- Focus on your healthy eating habits — Healthy eating can help combat depression & anxiety, hence upgrading sleep quality.

- Exercise enough — Only 27% of adults who reported zero days of exercise in the prior week said having “excellent” or “very good” sleep the night before vs. 41% of those who exercised five days.

- Get a high-quality, comfortable mattress — make sure it supports your back, doesn’t sink, and is the right size for you.

- Prioritize your sleep — Set a sleep and wake-up schedule and stick to it.

- Optimize your bedroom for sleep — ensure the temperature is right, eliminate electronics and other light sources, close the windows to reduce external noises, use light dimmers, aromatherapy diffuser, you know the means!

Best Kratom Strains to Help You Sleep

Kratom (Mitragyna speciosa) is a plant relative to coffee that has been used for centuries in Southeast Asia as a natural remedy for pain, anxiety, and sleep disorders.

Depending on the dose and the kratom strain you take, the effects can be stimulating or sedating. Among all kratom strains, red-veined kratom is the most adequate for insomnia and other sleep disorders.

Here are some of the best kratom strains for sleep:

- Red Maeng Da — This strain is favored for its strong sedative and relaxing effects. Since its effects are very potent, we recommend starting with a low dose until you find the desired effects.

→ Find This Strain in VIP Kratom.

- Red Malay — Users describe this strain as calming and relaxing. Thanks to its analgesic effects, Red Malay is excellent for those with sleeping problems due to chronic pain conditions.

→ Find This Strain in Kona Kratom.

- Red Bali — If you are just starting with kratom, Red Bali is perfect for beginners. This strain provides balanced pain-relieving and sleep-supporting effects.

→ Find This Strain in Star Kratom.

FAQs

How Many People Die in Their Sleep?

Although relatively rare, sudden nighttime death can be caused by various factors, including stroke, seizures, sedative overdose, and, more commonly, sudden heart attack. Sudden cardiac arrest (SCA) accounts for 90% of sudden and unexpected deaths at night [37].

A 2005 retrospective study found that patients with obstructive sleep apnea had a 2.57 times higher relative risk of SCA between midnight and 6 a.m. compared to the general population [38].

What is Sleep Apnea?

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a condition when the upper airway collapses and becomes blocked while a person is sleeping, causing breathing pauses (apneas), abnormally shallow breathing (hypopnea), or respiratory-related awakenings [39].

OSA is the most prevalent sleep-related breathing condition. OSA is more common in adult males but may also be present in women and children.

Between 15 – 30% of males and 10 – 15% of females in the U.S. have OSA. Aside from gender, the prevalence of OSA also differs by race, with African Americans having a higher prevalence than other populations.

The short-term prognosis for people with OSA is typically favorable. Treatments have improved symptoms in patients with moderate obstructive sleep apnea. However, if left untreated, sleep apnea might be fatal [39].

What Are the Best Natural Sleep Aids?

For thousands of years, societies worldwide have used natural remedies to ease sleeping troubles, pain, anxiety, and more. We have compiled a list of the top 12 herbs to help you sleep. Here a some of them:

Kratom

The alkaloids found in the kratom plant work by depressing the central nervous system and allowing us to relax and unwind. As mentioned before, red-vein kratom strains are best for inducing sleep and relaxation.

Valerian Root

Valerian root is a popular dietary supplement that can fight insomnia, especially in those who suffer from mood disorders such as depression and anxiety.

Lavender

With a long history of therapeutic usage, lavender is known to have soothing, antidepressant, anxiolytic, anticonvulsant, and antidepressant effects [40]. It is commonly used as essential oil directly rubbed onto the skin or inhaled through an aroma diffuser.

Final Thoughts: What the Numbers Say About Sleep Quality Worldwide

With the rise of technology, the COVID-19 pandemic, and other sources of stress and anxiety, the prevalence of sleep disorders is only getting higher and higher.

To get the most out of your daily life experience and improve your overall health, it is now more important than ever to prioritize your sleep and ensure you have a proper sleeping environment.

The data shows that people who prioritize their sleep tend to have healthier dietary habits, enjoy life more, worry less, and get sick less often.

International sleeping guidelines recommend around 7-8 hours of sleep each night.

If you want to try natural sleep aids, try red-veined kratom strains like Red Malay, Red Maeng Da, and Red Bali. Valerian root tea and lavender essential oil can also be beneficial.

- Phillips. (2019). The Global Pursuit of Better Sleep Health. https://www.usa.philips.com/c-dam/b2c/master/experience/smartsleep/world-sleep-day/2019/2019-philips-world-sleep-day-survey-results.pdf

- Casper-Gallup. (2022). The State of Sleep in America 2022 Report. https://www.gallup.com/analytics/390536/sleep-in-america-2022.aspx

- Chaput, J. P., Dutil, C., & Sampasa-Kanyinga, H. (2018). Sleeping hours: what is the ideal number, and how does age impact this? Nature and science of sleep, 10, 421.

- Philips. (2021). Seeking solutions: how COVID-19 changed sleep around the world. https://www.usa.philips.com/c-dam/b2c/master/experience/smartsleep/world-sleep-day/2021/philips-world-sleep-day-2021-report.pdf

- Black, D. W., & Grant, J. E. (2014). DSM-5® guidebook: the essential companion to the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. American Psychiatric Pub.

- Dopheide, J. A. (2020). Insomnia overview: epidemiology, pathophysiology, diagnosis and monitoring, and nonpharmacologic therapy. The American journal of managed care, 26(4 Suppl), S76-S84.

- Vahratian, A. (2017). Sleep duration and quality among women aged 40-59, by menopausal status. US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics.

- Phillips. (2019). Wake up call: global sleep satisfaction trends. https://www.philips.com/c-dam/b2c/master/experience/smartsleep/world-sleep-day/2020/2020-world-sleep-day-report.pdf

- Colten, H. R., & Altevogt, B. M. (2006). Extent and health consequences of chronic sleep loss and sleep disorders. Sleep disorders and sleep deprivation: an unmet public health problem, 55-135.

- Hasler, G., Buysse, D. J., Klaghofer, R., Gamma, A., Ajdacic, V., Eich, D., … & Angst, J. (2004). The association between short sleep duration and obesity in young adults: a 13-year prospective study. Sleep, 27(4), 661-666.

- Gottlieb, D. J., Punjabi, N. M., Newman, A. B., Resnick, H. E., Redline, S., Baldwin, C. M., & Nieto, F. J. (2005). Association of sleep time with diabetes mellitus and impaired glucose tolerance. Archives of internal medicine, 165(8), 863-867.

- Strine, T. W., & Chapman, D. P. (2005). Associations of frequent sleep insufficiency with health-related quality of life and health behaviors. Sleep medicine, 6(1), 23-27.

- Hasler, G., Buysse, D. J., Gamma, A., Ajdacic, V., Eich, D., Rössler, W., & Angst, J. (2005). Excessive daytime sleepiness in young adults: a 20-year prospective community study. The Journal of clinical psychiatry, 66(4), 6880.

- Alhola, Paula, and Päivi Polo-Kantola. “Sleep deprivation: Impact on cognitive performance.” Neuropsychiatric disease and treatment (2007).

- Taheri, M., & Arabameri, E. (2012). The effect of sleep deprivation on choice reaction time and anaerobic power of college student athletes. Asian journal of sports medicine, 3(1), 15.

- Olsen, O. K., Pallesen, S., & Jarle, E. (2010). The impact of partial sleep deprivation on moral reasoning in military officers. Sleep, 33(8), 1086-1090.

- Gilbert, S. S., van den Heuvel, C. J., Ferguson, S. A., & Dawson, D. (2004). Thermoregulation as a sleep signalling system. Sleep medicine reviews, 8(2), 81-93.

- Raymann, R. J., Swaab, D. F., & Van Someren, E. J. (2007). Skin temperature and sleep-onset latency: changes with age and insomnia. Physiology & behavior, 90(2-3), 257-266.

- Okamoto-Mizuno, K., & Mizuno, K. (2012). Effects of thermal environment on sleep and circadian rhythm. Journal of physiological anthropology, 31(1), 1-9.

- Kohlhuber, M., & Bolte, G. (2011). Influence of environmental noise on sleep quality and sleeping disorders-implications for health. Bundesgesundheitsblatt, Gesundheitsforschung, Gesundheitsschutz, 54(12), 1319-1324.

- Carter, N. L. (1996). Transportation noise, sleep, and possible after-effects. Environment International, 22(1), 105-116.

- Cho, Y., Ryu, S. H., Lee, B. R., Kim, K. H., Lee, E., & Choi, J. (2015). Effects of artificial light at night on human health: A literature review of observational and experimental studies applied to exposure assessment. Chronobiology international, 32(9), 1294-1310.

- Khan, M. N., Nock, R., & Gooneratne, N. S. (2015). Mobile devices and insomnia: Understanding risks and benefits. Current sleep medicine reports, 1(4), 226-231.

- Aurora, R. N., Collop, N. A., Jacobowitz, O., Thomas, S. M., Quan, S. F., & Aronsky, A. J. (2015). Quality measures for the care of adult patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Journal of clinical sleep medicine, 11(3), 357-383.

- Finan, P. H., Goodin, B. R., & Smith, M. T. (2013). The association of sleep and pain: an update and a path forward. The journal of pain, 14(12), 1539-1552.

- Morin, C. M., LeBlanc, M., Daley, M., Gregoire, J. P., & Merette, C. (2006). Epidemiology of insomnia: prevalence, self-help treatments, consultations, and determinants of help-seeking behaviors. Sleep medicine, 7(2), 123-130.

- Sleep and Mental Health Amidst the 2020 Coronavirus Pandemic. (n.d.). Sleep Cycle Alarm Clock. https://www.sleepcycle.com/coronavirus/

- Chong, Y., Fryar, C. D., & Gu, Q. (2013). Prescription sleep aid use among adults: United States, 2005-2010 (No. 2013). US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics.

- Akhtar, A. (2021). Americans have turned to melatonin to soothe pandemic-induced stress. Experts worry high demand, little federal oversight, and insufficient data leave the industry ripe for scams.

- Guadagna, S., Barattini, D. F., Rosu, S., & Ferini-Strambi, L. (2020). Plant extracts for sleep disturbances: A systematic review. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2020.

- Leach, M. J., & Page, A. T. (2015). Herbal medicine for insomnia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep medicine reviews, 24, 1-12.

- Malani, P., Solway, E., Singer, D., Kirch, M., & Clark, S. (2017). Trouble Sleeping? Don’t Assume it’s a Normal Part of Aging.

- Suardiaz-Muro, M., Morante-Ruiz, M., Ortega-Moreno, M., Ruiz, M. A., Martin-Plasencia, P., & Vela-Bueno, A. (2020). Sleep and academic performance in university students: a systematic review. Revista de Neurologia, 71(2), 43-53.

- Wheaton, A. G., Jones, S. E., Cooper, A. C., & Croft, J. B. (2018). Short sleep duration among middle school and high school students —United States, 2015. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 67(3), 85.

- Almojali, A. I., Almalki, S. A., Alothman, A. S., Masuadi, E. M., & Alaqeel, M. K. (2017). The prevalence and association of stress with sleep quality among medical students. Journal of epidemiology and global health, 7(3), 169-174.

- Abdullahzadeh, M., Matourypour, P., & Naji, S. A. (2017). Investigation effect of oral chamomilla on sleep quality in elderly people in Isfahan: A randomized control trial. Journal of education and health promotion, 6.

- Janine, A. (2022, January 26). How worried should you be about dying in your sleep? The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved August 24, 2022, from https://www.wsj.com/articles/how-worried-should-you-be-about-dying-in-your-sleep-11643205604

- Blackwell, J. N., Walker, M., Stafford, P., Estrada, S., Adabag, S., & Kwon, Y. (2019). Sleep apnea and sudden cardiac death. Circulation reports, CR-19.

- Cumpston, E., & Chen, P. (2021). Sleep Apnea Syndrome. In StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing.

- Koulivand, P. H., Khaleghi Ghadiri, M., & Gorji, A. (2013). Lavender and the nervous system. Evidence-based complementary and alternative medicine, 2013.